Introduction

An oil company can only exist if it has reserves and is able to keep production at targeted levels for a long period of time. If reserves and production dwindle, it is not only the attractiveness of such an independent oil company that comes into question but its whole existence.

The power structure of global oil markets is already undergoing a major transformation exemplified by the rising power of the National Oil Companies (NOCs) and the declining influence and power of International Oil Companies (IOCs). In coming years, this power structure is set for a major shakeup if the reserve lifespan of IOCs continues to decline.

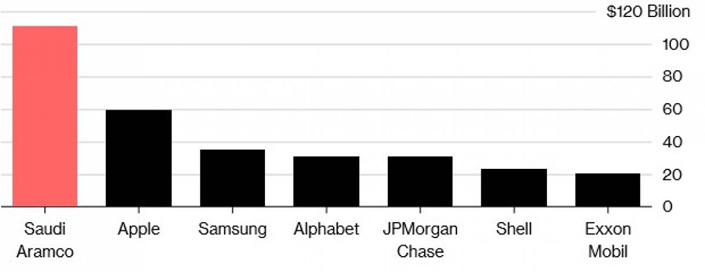

This shift could be evidenced from a comparison of Saudi Aramco’s net income in 2018 with ExxonMobil and Shell. Saudi Aramco’s net income of $111 bn was almost 6 times that of ExxonMobil ($20.8 billion) or Shell ($23.4 billion) (see Chart 1).

Chart 1

Net Income in 2018

Source: Oilprice.com accessed on 8 April, 2019

This transformation is being accelerated by low crude oil prices leading to declining investments in oil and gas projects, dwindling crude oil reserves of IOCs, pressure on IOCs to divest of their hydrocarbon assets and rising resource nationalism.

Whilst top IOCs such as Total, BP, Shell, Chevron, ENI, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, Equinore and Repsol have reserve to production (R/P) ratios ranging from 8.0-10.5 years according to CitiBank research, the NOCs of countries like Saudi Arabia, Iraq, UAE, Venezuela and Kuwait to name but a few have access to proven reserves whose R/P ratios range from 66-91 years at the 2019 production levels. 1

The oil reserves of IOCs are declining fast and they can’t replace what they are producing. Any new crude oil discoveries are being snapped up by the NOCs. Overall average IOCs’ reserves in place have fallen by 25% since 2015 with less than 10 years of total annual production available. 2

This transformation has been inevitable since the birth of OPEC just over sixty years ago. Before 1960, the “Seven Sisters” (Exxon, Mobil, Chevron, Gulf Oil, Texaco, BP and Shell) controlled 85% of the global oil reserves. Since then, industry dominance has shifted to OPEC and state-owned oil and gas companies. By 2012 only 7% of the world's known oil reserves were in countries that allowed IOCs free rein. Fully 65% were in the hands of NOCs.

The formation of OPEC marked a turning point toward national sovereignty over natural resources and OPEC decisions have come to play a prominent role in the global oil market and international relations.

Various factors such as high oil prices, increased industry competition, the lack of alternative investment options for IOCs and rising resource nationalism have weakened the bargaining power of IOCs with oil-exporting countries and NOCs. Their future as viable business entities is being further compromised by the changing policy and environmental regulations in response to global climate change.

Impact of oil prices

High oil prices have enhanced the bargaining power of oil-exporting countries. As a result, major IOCs have struggled to secure access to new oil reserves and their production has dropped in recent years.

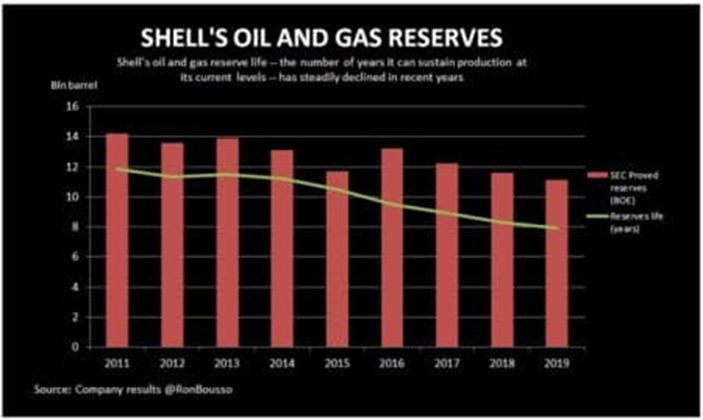

For instance, oil supermajor Shell said in its Energy Transition Strategy that it will put to a non-binding shareholder vote next month that it expects to have produced 75% of its current proven oil and gas reserves by 2030, and only around 3% after 2040. 3

In 2020, Shell’s proven reserves (taking production into account) decreased by 1.972 billion barrels of oil equivalent (boe) to 9.124 billion boe at December 31, 2020 according to the company’s annual report. 4

Growing Resource Nationalism

Resource nationalism has been on the rise around the world underpinned by governments wanting to fully control whatever hydrocarbons and mineral resources they have in order to maximize their revenues, growing global demand for these resources and also growing influence of the NOCs. That is why resource nationalism has become a major threat for the IOCs.

Three basic underlying factors influenced the shift of the balance of power in favour of IOCs in the second part of the 1980s and in the 1990s. First, low oil prices resulted in host countries’ desperate need for foreign investment. Second, IOCs had no competition from other companies, such as oil-importing NOCs, when investing in host countries. Third, IOCs were able to pursue alternative investment options if not permitted favourable entry to a particular host state.

Resurgent resource nationalism represents the underlying factor behind the possible demise of some major IOCs in this decade. The main reason for this resurgence has been the high price of oil. When oil prices were low, as in the late 1980s and for much of the 1990s, IOCs were courted by oil-rich states to develop their national resources. However, when prices started to rise, as they did in the early years of the 21st century, host governments started to rethink their contracts and seek higher taxes and royalties. Thus, it is natural that during a period of high prices the phenomenon of resource nationalism returns.

As a result of resource nationalism, IOCs are not welcome in the major oil-producing regions of the world, the Middle East, North Africa and much of Latin America. These regions in which IOCs most want to operate, are becoming extremely difficult operating environments due to political and regulatory constraints. Much of the major IOCs’ production comes nowadays from the North Slope in Alaska, the Gulf of Mexico and the North Sea, areas which are witnessing rapid decline and where production is becoming increasingly more expensive. North America and the North Sea account for an estimated 60% of the IOCs’ oil.

Profit margins per barrel are also a major investment issue as IOCs have been looking at the more challenging environments, such as deepwater, offshore, Arctic, or shale, while NOCs still have major conventional reserves in place.

Industry Competition

Major IOCs also face increasing competition. NOCs have grand ambitions and compete with the majors by developing new oil reserves overseas and investing in international refining and retail activities with a long-term business perspective. 5

Technology, expertise, capital and access to markets are now easily sourced from independent operators and oil-service companies such as Halliburton and Schlumberger, but, most importantly, from countries like China, Russia and Brazil.

For instance, Chinese oil companies have in recent years been spending billions of dollars on a global scramble for oil to feed China’s booming economy. They have the ability to obtain government loans at little or no interest. The Government’s energy security policy is aimed at developing multiple import sources and routes and building up reserves to avoid unexpected interruption.

Driven by the Government’s policy, China’s oil companies have acquired growing equity oil stakes and long-term crude oil contracts and have signed ‘strategic’ alliances with oil producers in all of the world’s major oil-producing regions. In doing so, they have triumphed over major IOCs in various bidding and bargaining events in many oil-producing countries, particularly in Iran, Iraq and Venezuela.

Global Energy Transition

Some analysts have already claimed that the current reserve crisis is no real issue, as most IOCs are going through an energy-transition phase. However, to invest in the energy transition these companies need plenty of cash to cope with the planned multi-billion-dollar wind, solar, and hydrogen projects, while also keeping investors and shareholders happy. Almost 80% of this cash flow is generated from oil and gas. As one chairman of an IOC put it succinctly “Black pays for Green”. 6

Major IOCs have been earning an estimated 20% return on investment, a healthy figure by industry standards. Without doubt, high oil prices have enabled them to generate unprecedented profits but they have also fuelled a resurgence of resource nationalism, which along with increased industry competition severely limited areas open to IOC investment. It is becoming increasingly difficult for IOCs to find attractive ways to reinvest their profits and it will not get easier given that there are limited drilling prospects.

Climate change mitigation is becoming one of the principal challenges for major IOCs. New and strengthened climate change mitigation policy and environmental regulations aimed at accelerating energy transition are likely to have negative consequences for major IOCs.

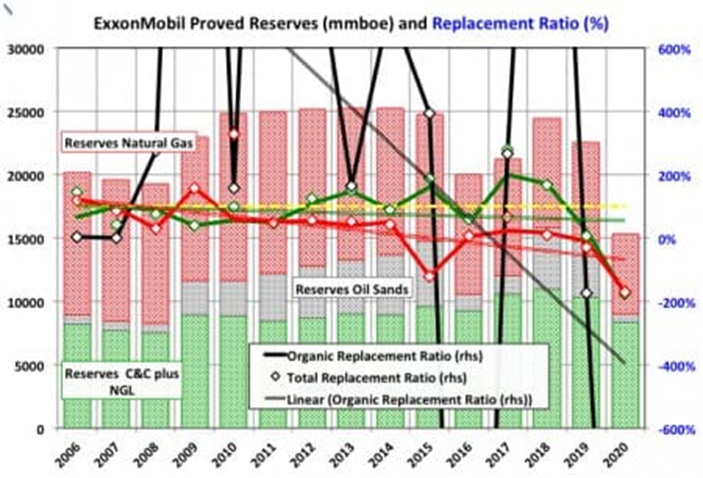

Reserve Replacement

In the global oil industry, reserve replacement is the best guide to whether a company will be able to maintain or enhance its oil production in the future’. A healthy reserve replacement ratio should always be over 100%. Between 1998 and 2002, top IOCs replaced 99.7% of oil produced. This declined to 51.7% between 2003 and 2007. 7 Overall average IOCs’ reserves in place have fallen by 25% since 2015 with less than 10 years of total annual production available.

Charts 2 & 3 depict Shell’s and ExxonMobil’s reserve replacement but they are all representative of major IOCs’ as well.

Chart 2

Source: Courtesy of Oilprice.com on 12 April 2021.

Chart 3

Source: Courtesy of Oilprice.com on 12 April 2021.

The largest and the cheapest oil reserves to produce are located in the Arab Gulf region and Russia and not in the hands of the most efficient and best-capitalised firms, the IOCs. Instead, they are controlled by NOCs and governments who can self-finance the whole operation from reserves to pipelines.

Could IOCs Weather the Storm?

IOCs face a variety of problems ranging from replacing reserves to responding to new environmental regulations and coping with increasing competition from NOCs.

In order to remain viable business entities in coming decades, major IOCs need to increase their reserve base and oil production in order to generate profits. However, in future, the industry environment is set to become even more challenging for the IOCs.

The rise of the NOCs and resource nationalism will ensure that major IOCs will not be able to secure favourable deals in future. The adverse impacts are likely to destabilise and undermine their future viability as business entities. As a result, the next fall in oil prices could lead to mega-mergers among the IOCs if not the demise of some.

Major NOCs are challenging the IOCs on their own turf. This is exacerbated by NOCs’ access to cheap government finance, which provides them with an unfair advantage vis-à-vis IOCs in bidding for concessions. Against this, market forces and private enterprise might not be capable on their own to solve IOCs’ problems in the current decade.

One possible strategy to make IOCs more competitive could be for their home governments to take partial control thus transforming them into IOC-NOC hybrids. 8

Example are Russian giant oil and gas companies Rosneft and Gazprom. They are private companies in which the Russian government is a shareholder. They could be a role model for other IOCs seeking to redefine themselves and their roles in the new global landscape.

Both Rosneft and Gazprom have built up diversified business empires that now span the globe. They have interests in the Caspian, Middle East, Central Europe, North Africa and South America. Unlike those of major IOCs, in recent years, their oil and gas reserves have increased steadily and their access to markets improved dramatically.

It is therefore suggested that one way to salvage the IOCs in the long-term would be for their home governments to assume partial control, thus creating NOC-IOC hybrids, which may be more resilient in dealing with the challenges ahead.

Conclusions

The rivalry between IOCs and NOCs over reserves and dominance of the global oil market will continue as long as oil occupies a central position in the global economy.

While the IOCs have more experience and expertise in the global oil market having been operating for decades in different environs around the world and also the most advanced technology to explore and produce oil and gas, the NOCs have the ultimate advantage of owning the bulk of the world’s proven oil reserves. Moreover, with rising oil prices, they can afford to buy expertise and the latest technology and also extend their reach when it comes to investment around the world.

That is why NOCs will prevail over IOCs.

Footnotes

- BP Statistical Review of World Energy, June 2020, p.14.

- “Big Oil’s Dwindling Reserves Are a Major Problem” posted by oilprice.com on 12 April 2021 and accessed on 13 April 2021.

- “Shell to Exhaust Dwindling Oil & Gas Reserves by 2040” posted by oilprice.com on 15 April 2021 and accessed on 15 April 2021.

- Ibid.

- Vlado Vivoda, “Resource Nationalism, Bargaining and International Oil Companies: Challenges & Change in the New Millennium” published by New Poiltical Economy at the University of South Australia in 2009 and accessed from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/36408 on 13 April 2021.

- Big Oil’s Dwindling Reserves Are a Major Problem”.

- Vlado Vivoda “Resource Nationalism, Bargaining and International Oil Companies: Challenges & Change in the New Millennium”.

- Ibid.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

*Dr. Mamdouh G. Salameh is an international oil economist. He is one of the world’s leading experts on oil.

He is also a visiting professor of energy economics at ESCP Business School in London.

Disclaimer: "The contents of this article are the author's sole responsibility. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Hellenic Association for Energy Economics or any of its Members".